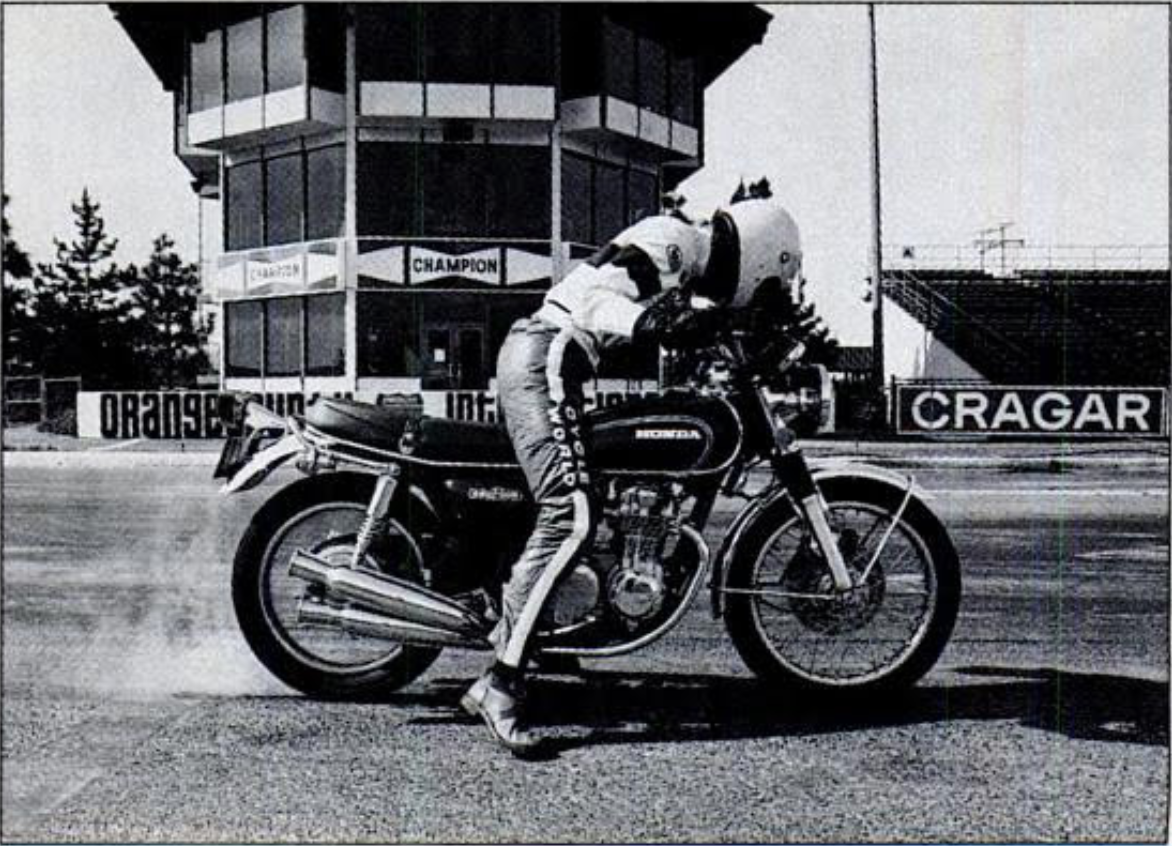

Hints of the story behind a Honda CB550 that is what it shouldn’t be.

When I went to look at a cb550 after it caught my attention browsing through the classifieds, I saw a rugged, characterful and misused motor with some semblance of charm. It was icy outside, so after taking the bike indoors to let it thaw, I returned the following day to hear it run. With the tap of a button the engine roared to life. Within an instant a connection formed, almost like meeting an old friend after many years.

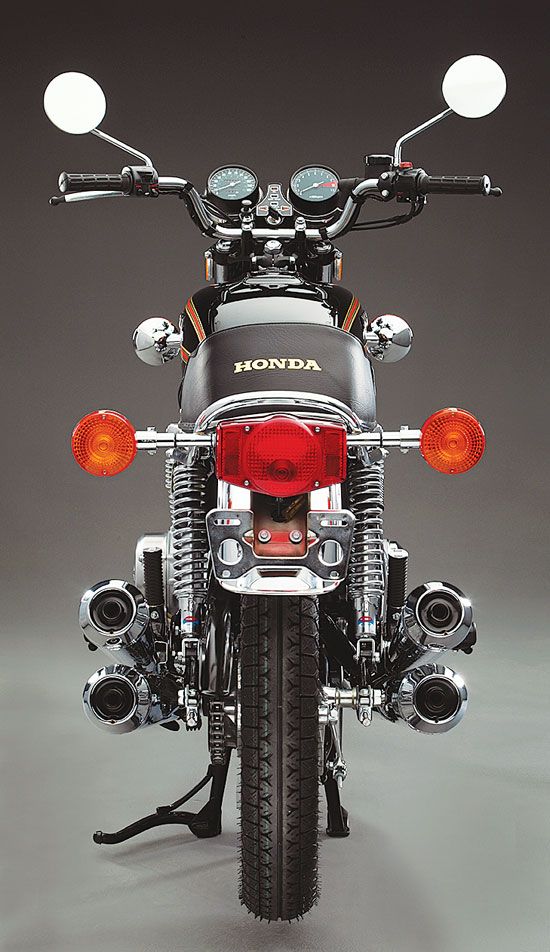

The year was 2019 and with 45 years under its belt, having been built in Japan and driven across North America, I knew it would have stories. If only it could speak.

Laden with dirt, grease and wax the bike looked worse for wear. Tom, the prior owner of the bike, mentioned to me that he had rented to it to a movie production and their costume and set team had had their way. I couldn’t wait to get a rag and some soap to it.

But that’s when hints of a story began to emerge.

I noticed that the badly painted gas tank (again thanks in part to the apparent movie set team) had bondo cracks. So I called Bill, a talented dent repair specialist, if he would be able to take a look at it. “Sure,” he said, being a fellow bike guy. But mentioned that gas tanks were anything but easy when it came to popping dents.

Well that night I began the arduous work of sanding the bondo from the tank and prepping it for Bill. Yet as I peeled away the layers of old repairs and paint, more and more dents appeared. Clearly this bike had seen adventure.

Bill’s face lit with amazement when I showed him the tank. But faithful to his word he did his best. I was blown away by the difference. The once brutally damaged tank was enhanced to a patina that matched its age. I could almost hear my new old friend smile.

Tom had mentioned the bike was running rich. So I carefully tore open the carburetors. Meticulously organizing as I went. Someone, long ago, had rebuilt these carburetors before me. And had used some sort of seal gasket glue on everything, filling critical pathways and even covering the holes of the drain screws – which had been glued closed. It was obvious that others had since tried loosening them. Fortunately I had this incredible cleaner on hand. It’s probably toxic and deadly but eats through anything, so I love it.

I found the source of the fuel mixture issue. The number 4 gasket was missing the needle. That would do it. Clearly someone else had discovered this too. The piston in the same carburetor was dented and bent from what appears to have been the work of a nonsamurai master. Fortunately, a file and carb cleaner made short work of the worst of it and the piston was removed. After addressing any issues, fixing all bent components and bolting it back together the carburetor looked and functioned as good as new… almost. The number 4 exhaust was cold after firing up the engine. Fortunately I was able to quickly find a replacement piston on eBay and then the engine ran without fault.

I thought it odd that the inner workings of the engine seemed to be in better condition than the carburetor.

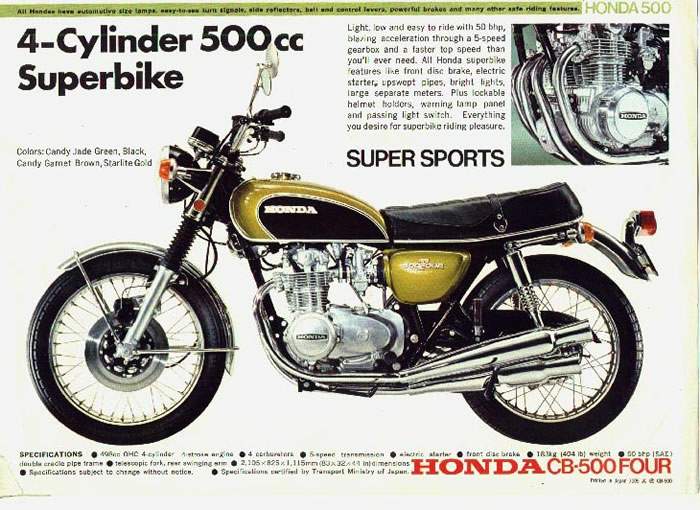

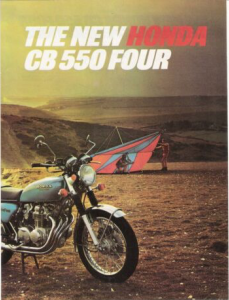

Later, I began the simple task of bleeding and rebuilding the front forks. I ran into my first snag. The fork screws were sealed with the same gasket glue as the carburetor. And then, to my surprise, the lower springs were missing. I quickly checked online to see if any CB550s came stock without lower springs in their forks. Sure enough the CB550f did.

Earlier I had noticed the original color of the bike was said to be blue. According to insurance files it had always been blue. I searched online to see if any CB550fours were blue by stock. At first my search would turn up fruitless.

The rear passenger frame mounts had long since been removed and I hadn’t checked the serial number of the bike. Suddenly I began to fear that my bike wasn’t what I thought it was.

Grabbing my papers I ran to the garage and scanned the front of the bike. There it was, the number stamped into the front. But I couldn’t see the vin plate which concerned me. Turning the handlebars I saw thick black tape covering half of the front of the frame. More concerning still.

I pealed back the tape to reveal a shiny original vin plate matching the vin stamped on the frame and the vin of the papers. Anyone standing nearby would have heard an audible sigh of relief.

Now I began to wonder about the engine. Fortunately, I had noticed on the website of a European Honda parts supplier a document of all the frame and engine numbers. I compared the number of the engine with frame. The years matched. Then I noticed they also documented the carburetor number as well – which surprised me.

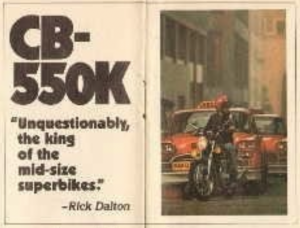

But as I checked the numbers, the carburetor matched a CB550f, like the forks. Another story emerged. Clearly the forks and carburetor were most likely from the same bike and for whatever reason had replaced the original ones on this bike.

That would explain why the motor seemed in better shape than the carbs. And why I couldn’t find any traces of that gasket glue anywhere else on the bike or engine.

But again I wondered about the color. I knew a CB550f came in blue. Perhaps that was the confusion. But no, the fuel tank was a different shape, rather than having the classic styling with the chrome lid, the CB550f was a more modern shape and had a hidden cap. Secondly, while the frame is nearly identical between the bikes, the mounting points are not. And the CB550f side panels didn’t fit the my frame.

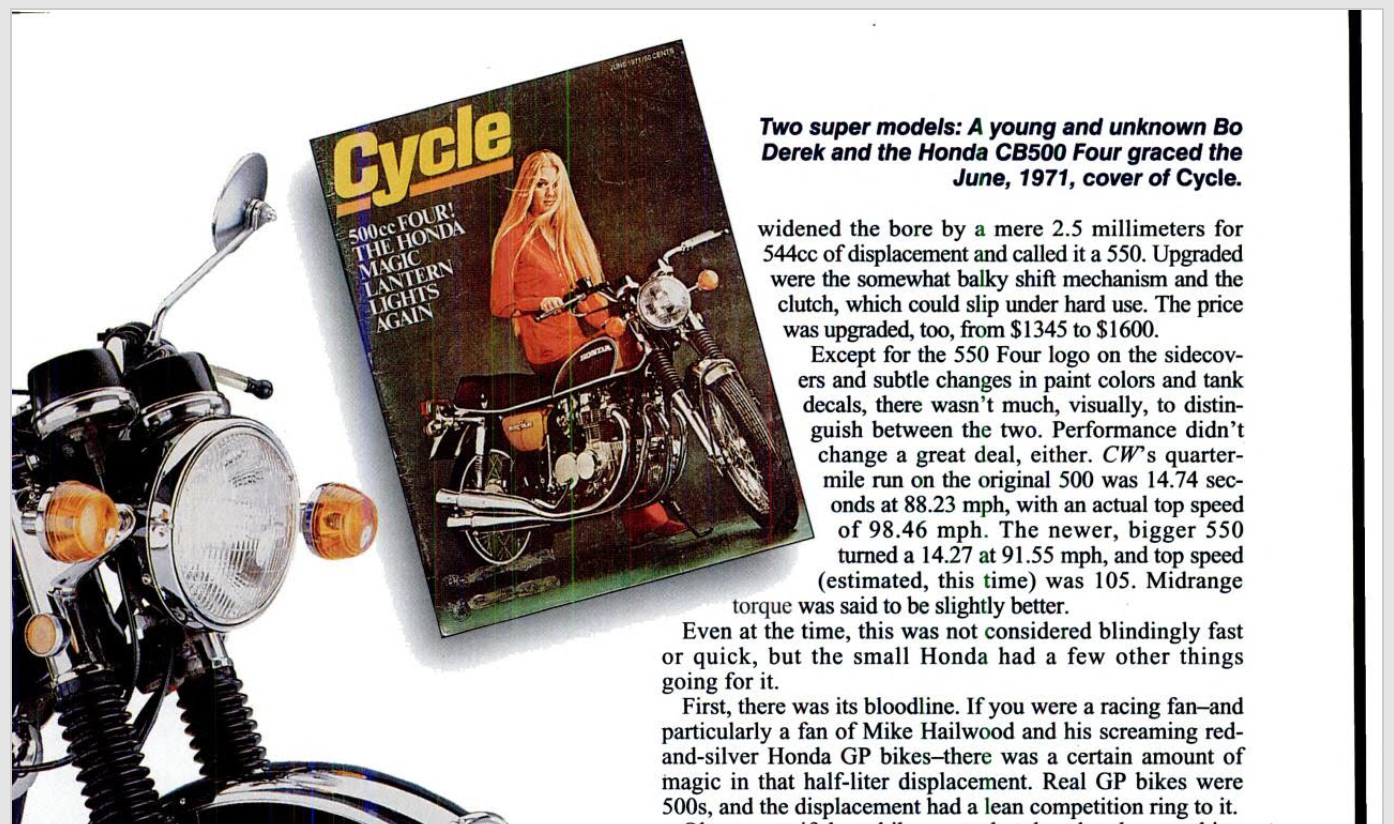

Then by happenstance I stumbled upon a 7 year old video on Youtube of an original blue CB550. It appeared to be the same year as my own. Curious, I went back to the garage and examined my parts. The side cover was cracked and beneath layers of primer and repaints, there as clear as day was a metallic blue. I flipped over my fuel tank as well, and sure enough I could see metallic blue overspray. So definitely the original tank. I did also spot green overspray as well. Perhaps there was an option to custom paint the bike when purchasing it? Or possibly they swapped a cb500 tank and side panels when purchasing the bike? Perhaps someone reading this would know if that is something that was done in the 70s.

The bike also had a blue face on the odometer gauge with miles matching the papers. Every reference of the bike I can find in bike reviews say the gauges were green. Now I know that my odometer could have easily been changed. So I did some more research on forums, classifieds and Youtube and have since found many 1974/75 cb550s with blue gauges. So again, an unlikely surprise, but it looks to be original to the bike.

Remember how the tank was badly dented? Well, the story continues. Excited to get into things I immediately began giving the old beast a thorough cleaning. There was dirt everywhere with sand and grit found in every crevice of the engine body.

The bike had been given an intentionally “rustic” paint job for the movie. Where black was painted over silver and then sanded back to reveal the silver in spots. Again, apparently to serve the look of the film. But, despite soap being thrown in its direction the bike still looked dirty after each wash. So a quick trip to my local auto paints store and I returned with high quality black paint for rims. Something that would endure the elements until I would be able to powder coat it down the road.

Well, removing the gas tank revealed a very silver frame indeed. All the hardware such as the battery holder and metal clips were also painted in silver. And the quality was too good to fit the work of the movie look. This had been done before.

The more I investigated the frame and paint the more I was impressed with the workmanship. Someone at some point in its history cared for this bike.

But the cleaning revealed something else too. I noticed some dents on the side of the engine fins. But as the wax was removed the dents turned into chips and cracks. This engine had been through war. The majority of the wear was on the same side where the gas tank had most of its dents.

Had someone used this as an enduro bike? It’s possible.

In many ways, rediscovering an old bike is like unearthing an archeological site. One must rely on the remnants of clues to share the stories long forgotten or untold.

Yet it’s these discoveries that hint to the story and soul of the bike. The peculiarities of the engine. The way it sits on the road. And the charm of its character. Much like an old friend. Battered, bruised but no worse for wear.

And also, much like an old friend. Occasionally they share stories that almost seem too interesting to be true. Yet they are.

Many movies are filmed in the area I live. Mostly small production indie films. Some of my friends are filmmakers. So when Tom remarked that this bike was used on set it didn’t grab my attention. That is, until I began discovering more about the peculiar hints of history that this bike seemed to have. An unlikely original paint color. An unlikely pairing of forks and carburetor. An unlikely speedometer. And even an unlikely turn of events – from the pride of someone’s garage to become what appears to be an enduro to then appear on a film set. All of which was unlikely. But evidence suggested otherwise.

And like all nagging thoughts it asked to be investigated.

It turns out it was in a movie, titled Endless. The movie was released in 2020. And stared Nicholas Hamilton (from IT) Alexandra Shipp (Storm on X-Men).

And surprise surprise, the bike is featured on the cover of the film.

Now I know that the bike was in a movie. I know that it was painted blue. I also know that it has a CB550f fork and carburetor. And I know that it was owned by a chef at some point. Tom told me. But I don’t know that it was used as a dirt tracker or that it was stored in a garage. I only have the clues. But isn’t that what great stories are. Just enough to guide you along and just enough to let your mind wonder.

Clearly, however it was Honda and they had plans of one day returning.

Clearly, however it was Honda and they had plans of one day returning.

A quick glance at

A quick glance at